The Emerging EUDI Framework and missing the Trust Anchors

Europe is on the path to a unified digital identity ecosystem with the European Digital Identity (EUDI) Wallet initiative. Under eIDAS 2.0 (the updated EU regulation), Member States must offer citizens a certified digital ID wallet by 2027. Critically, the EUDI Wallet will be free of charge for citizens and voluntary to use. It aims to let people securely store and share credentials like person identification data (PID) or attestations of attributes (EAA/QEAA) across the EU. However, while the regulations set high-level rules, the “trust model” – the governance and business framework that makes the wallet ecosystem viable – is still a work in progress. The full EUDI trust infrastructure (e.g. trusted lists of issuers, rules for credential use, etc.) will take time to implement, and until it is in place, there is effectively a trust gap in the digital identity landscape.

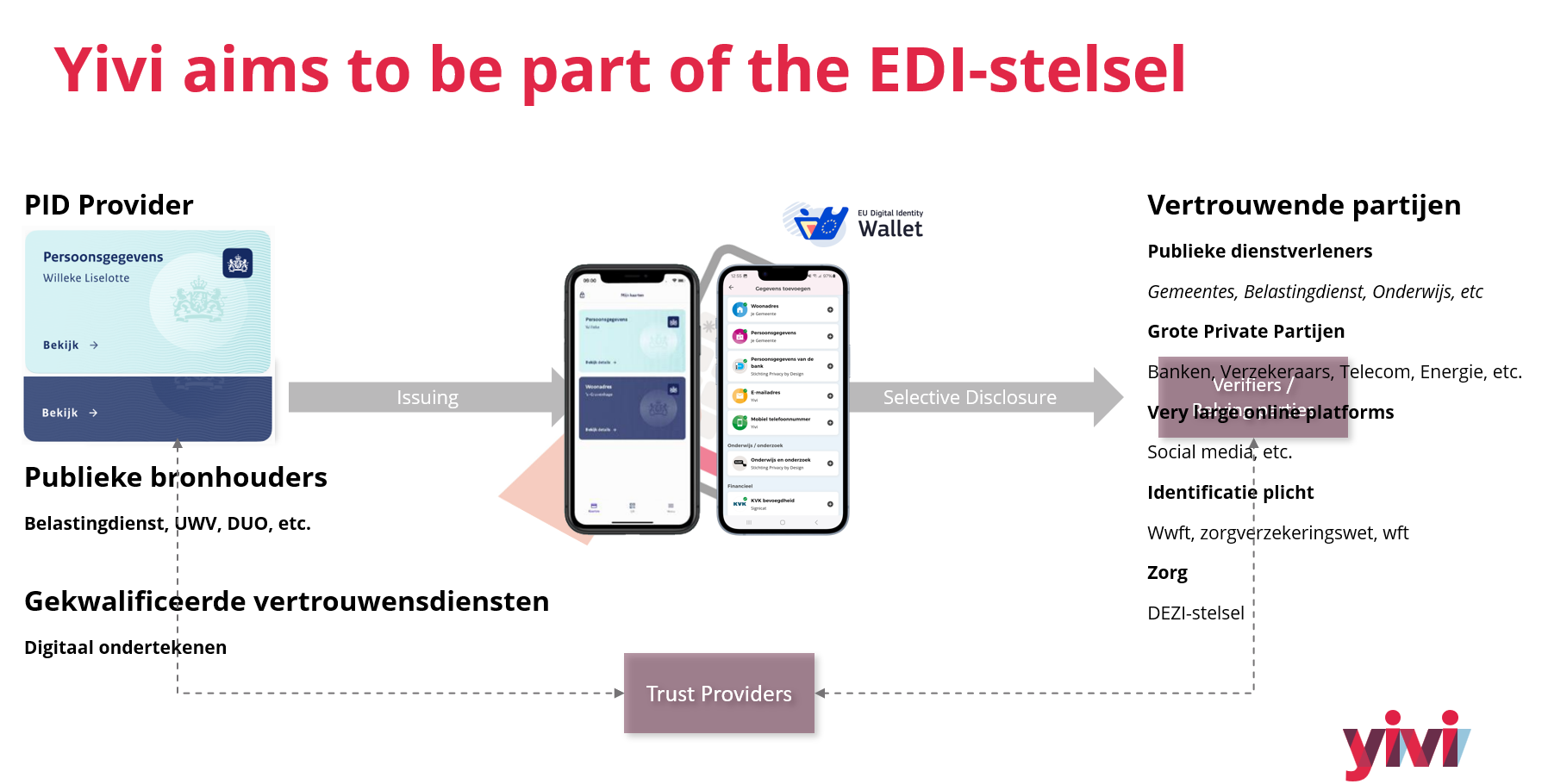

In the Netherlands, for example, work is underway on the EDI-stelsel, a nationally regulated framework that will underpin the NL Wallet (the Dutch EUDI Wallet implementation) and private wallets. This will be a highly regulated environment for exchanging identity data, providing official credentials like PIDs and public-sector attestations. Yet, as of now there is no comprehensive trust model operational for wide-scale use – the policies, certifications, and economic model are still being defined. In the meantime, alternative trust systems are filling the gap. One prominent example is Yivi, we have been operational for several years. Yivi’s scheme is fully open source and has an established trust framework (with the Privacy by Design Foundation as its trust anchor) that welcomes participants to issue and verify credentials. In other words, while Europe waits for the official EUDI trust model to materialize, solutions like Yivi are demonstrating that a functional trust ecosystem can exist today.

The need to stack trust systems

Given the current landscape, it’s becoming clear that “stacking” trust systems will be important. No single trust model will cover all use cases in the near future. The EUDI Wallet’s official trust framework will focus on government-recognized credentials (e.g. national ID, driver’s license, etvc.) under strict rules. But many other identity credentials and use cases – especially those in the private sector or those involving some form of payment or added value – may fall outside the scope of the official system. By stacking trust systems, we mean enabling multiple coexisting trust frameworks to work in parallel or in layers. For instance, a wallet could support the government-led EUDI trust scheme and one or more proprietary or open schemes for other credentials. This is important to maximize the wallet’s usefulness: a citizen might carry a government-issued PID in the same wallet as bank credentials, employer attestations, loyalty club memberships, or other certificates that come from different trust networks.

Stacking trust systems also ensures continuity and innovation. Because the EUDI model is not fully operational yet, users and businesses need something in the interim. An open scheme like Yivi’s can operate now and later interoperate with the EUDI system when it’s ready. Yivi’s vision explicitly acknowledges this: Yivi plans to align with Dutch and EU schemes so that its users can seamlessly use credentials from multiple ecosystems – public or private – without friction. In practice, this means Yivi’s wallet could hold a Dutch government-issued PID alongside other credentials issued under Yivi’s own trust scheme or other industry trust frameworks. Trust scheme pluralism is seen as critical to maintaining openness and user choice. The bottom line is that by stacking trust systems, we ensure that no single model’s limitations (be it regulatory delay or limited scope) hold back the overall growth of digital identity usage. Users can benefit from the strengths of each system: the broad acceptance and legal assurance of the EUDI credentials, and the flexibility or niche services provided by alternative schemes.

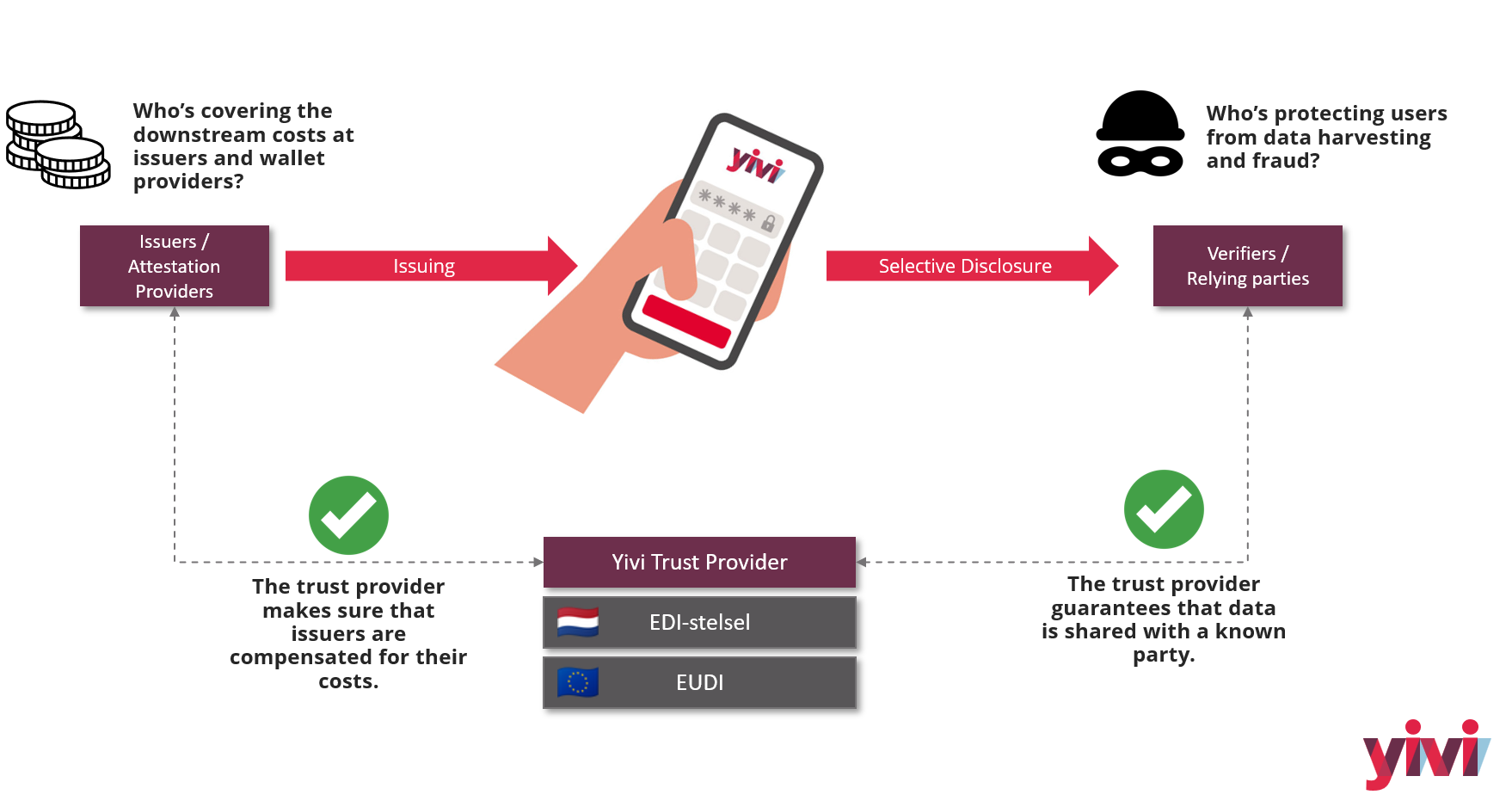

Business model challenges in Digital Wallet Ecosystems

While digital identity wallets deliver convenience and security, figuring out who pays for these services is a major challenge. Issuing a credential, running a wallet service, and verifying credentials all incur costs, whether it’s operational IT costs, customer support, or even third-party verification steps. In today’s identity ecosystem, different players have various business models, often subscription or transaction-fee based. With the advent of government-backed wallets, some assumptions are shifting.

Notably, the new EU regulation is pushing for broad adoption by requiring certain service providers to accept the EUDI Wallet. For example, “very large online platforms” will be obligated to accept EUDI Wallet authentication for their users. If an online platform (say a social network or e-commerce giant) must allow login or identity verification via the EU wallet, this raises the question: can any party charge for that transaction? Probably not in the core EUDI model – otherwise mandatory acceptance would effectively impose costs on private-sector relying parties without their consent. Indeed, the spirit of the regulation is to make digital ID as accessible as presenting a passport – you generally don’t pay a fee each time you show your ID. Moreover, as mentioned, the wallet is free for citizens to use by law. This strongly implies that the infrastructure enabling basic identity transactions should be provided as a public good, or at least not on a per-use charge to the end-user.

Because of this, we believe that monetized credentials (pay-per-use identity data) will not be anytime soon part of the official EUDI trust model. The government-issued or qualified credentials in the EUDI Wallet are likely to be provided without usage fees – funded by the public sector or under a fixed-cost model – to encourage universal adoption. If a bank, for instance, is required to accept a European Digital Identity credential, it would be unreasonable for that bank to also have to pay a third-party fee for each verification on a mandatory government service. Thus, any monetization in the ecosystem will probably happen in proprietary or supplemental trust models built on top of the EUDI framework, rather than within the core trust framework itself.

“We believe that monetized credentials (pay-per-use identity data) will not be part of the official EUDI trust model.”

This also hints at why government-provided wallets might be limited in scope of use cases. They will focus on high-value, broad public-interest credentials, where cost is covered by the state. But consider credentials that have an inherent commercial aspect, for example, a professional license that an industry body might want to charge for verifying, or an insurance credential that a company issues as a paid service. Such data likely won’t be included in the strictly regulated EDI-stelsel/EUDI trust model if including them would introduce pay-per-use mechanics or complex business rules. Instead, those will live in parallel schemes. In short, the official wallets will cover the “commons” of identity data, and other ecosystems will handle the monetized, proprietary, or value-added credentials.

Why Monetization Might Live Outside the Official Trust Model

The EU’s Architectural Reference Framework (ARF) for the EUDI Wallet emphasizes privacy and security. These principles don’t mesh well with a built-in profit model – especially one where an intermediary might keep logs of every verification to bill someone, as that could create a privacy hotspot. Indeed, a key requirement is preventing issuers and verifiers from tracking user behavior across services. That means the wallet system should ideally not generate a detailed audit trail of when and where each credential was used, at least not one accessible to a central party. This design goal is great for privacy, but it complicates monetization because tracking usage is exactly what you need if you want to charge per use.

For these reasons, we expect monetization schemes to be layered on top of the base wallet infrastructure. Proprietary trust models could, for example, require relying parties to register and agree to pay for certain premium credentials or verifications. They might operate as closed ecosystems (similar to app stores or data exchanges) where participants settle payments among themselves, rather than as part of the open EUDI transactions. An example is the approach some innovators are taking: Dock and Yivi, for instance, propose an “ecosystem-bound” credential model that restricts who can verify a credential to paying members of a network, thereby enabling issuers and ecosystem operators to get compensated. Such proprietary models can enforce payments within a closed trust circle without altering how the public EUDI wallet works for general credentials.

The consequence is that government wallets may deliberately limit their use cases. Any data or credential that requires a fee to verify will likely not be part of the government’s default offerings. Instead, if a user needs to share a piece of information that a third-party charges for, that transaction will happen through an add-on service or a different wallet app/plugin that interfaces with the main wallet. For example, the Dutch NL-Wallet under the EDI-stelsel will handle things like citizen ID or citizen attributes in a regulated way, but you might not find, say, a commercial credit score credential in it if that credit bureau expects to be paid per check. Those kinds of credentials would reside in other apps or be added via third-party digital identity providers that sit atop the EUDI framework.

In sum, the official trust model is likely to remain fee-free at the point of use, pushing any pay-per-use monetization to the edges of the ecosystem. This ensures that essential interactions (like proving your age or identity to a government service or a mandated private service) remain frictionless and accessible, while still allowing room for companies to build business models around more specialized identity data in a compatible way.

Key Questions for Transaction-Based Pricing Models

If an identity provider or wallet platform does decide to pursue a transaction-based pricing model (outside the core EUDI system), there are several fundamental questions and challenges they must address. Below we outline these key considerations:

-

Who will cover the costs – the user or the relying party?

In most cases, it’s undesirable to charge the end-user for each identity transaction. Imagine having to pay every time you share your ID – users would simply avoid it. The more practical approach is to have the relying party (service provider) pay, since they are the ones who benefit directly from receiving high-quality, verified data. The relying party uses that trusted data to streamline their business (e.g. faster onboarding, reduced fraud, compliance with KYC regulations), which brings them value. Thus, it makes sense for them to bear the cost. This mirrors many existing models: for example, employers pay for background checks on prospective employees, or e-commerce sites pay for credit card verification – not the individual user. A digital analogy: verifying a user’s phone number via SMS typically costs a business a few euro-cents per message (on the order of €0.05–€0.10 per verification SMS). Users aren’t charged for that text message – the service absorbs the cost to improve its security. The same principle should apply to credential verification. Ultimately, if identity wallets are to gain adoption, making users insert coins for every credential presentation is a non-starter. The relying parties should fund the system, as an investment in better data and lower risk. -

What should trigger a charge – issuing a credential or disclosing (presenting) it?

One might initially wonder if issuers could charge for issuance of credentials (e.g. “Pay €5 to get your digital diploma credential”). However, issuances often happen without a specific relying party requesting them; users can proactively obtain credentials and store them for future use. Charging at issuance would either burden the user (again, not ideal) or require some third party to sponsor it with no guarantee of immediate benefit. Moreover, a single credential might be used at dozens of different relying parties over its lifetime. If the issuer only charged once at issuance, all subsequent uses would be “free rides” – good for relying parties, but the issuer might not be rewarded for the ongoing value that credential provides. Therefore, the consensus in emerging business models is to charge for disclosures (verifications) instead. Each time a credential is presented and verified by a relying party, that relying party would pay a small fee for the service. This approach aligns costs with actual usage and value. Yes, this means a credential can be reused multiple times without the issuer having to re-issue it each time – indeed, reuse is a feature, not a bug. But it also means the price per disclosure might become very low if credentials are frequently reused. We may see market forces drive the price-per-verification downwards (a “race to the bottom” in pricing) as wallet adoption scales up and verifications become common commodities. Relying parties will only pay significant fees if the credential is high-value or infrequently used; otherwise, volume and competition will push prices to minimal levels (perhaps akin to that €0.08 SMS cost or even less). -

Who counts the disclosures (verifications)?

If we are charging per disclosure event, we need an accurate count of how many times each relying party actually consumed a credential. A naive solution is “let the wallet or issuer count it.” But this raises a serious privacy concern: if the wallet platform or credential issuer is tracking every disclosure, they learn where, when, and how often a user is presenting credentials. This effectively creates a log of the user’s behavior across various services – something both users and regulators would frown upon. The whole point of decentralized identity is to enhance user privacy (e.g., unlinkability, meaning one verifier shouldn’t know where else you’ve used the credential). Having a central counter would reintroduce a centralized surveillance point. Therefore, the preferred approach is that the relying party itself should do the counting of how many verifications it performed. The relying party is already party to the transaction (the user is interacting with them), so no new privacy breach is introduced if they keep track of how many times they invoked a credential check. The wallet or issuer, on the other hand, ideally should not learn about these individual events. In summary, for privacy, any “metering” of usage should happen on the verifier’s side, not by the wallet provider tracking the user. -

How do we ensure trust in the counts (and payments) if the relying party is self-reporting?

Here we hit a paradox: the relying party is the one paying per disclosure and also the one counting how many disclosures took place. If left entirely to self-reporting, there’s an obvious incentive problem – a dishonest relying party might under-report usage to reduce fees, or disputes could arise about the accuracy of the counts. In a traditional setting, this is solved by audits or technical enforcement. So, this challenge requires a clever solution in a decentralized identity context.

By addressing these four questions – payer, charging point, metering, and verification of usage – an identity ecosystem can create a viable transaction-based revenue model that doesn’t violate privacy. It’s worth noting that any such system should be as transparent and lightweight as possible. Overly complex or intrusive mechanisms would discourage participation. The ideal scenario is that from the end-user’s perspective, nothing changes (they use their wallet freely, consenting to share data when needed), while behind the scenes the relying parties and issuers have a clear arrangement to settle the costs of providing that trusted data.

Case Study: Yivi’s Trust Scheme and Sustainable Monetization

Let’s turn to a real-world example of these concepts in action. Yivi is a Dutch digital identity wallet that has been a pioneer in the field of attribute-based credentials and privacy-by-design. Yivi provides a fully open-source wallet and ecosystem where users can collect credentials from various issuers and selectively disclose them to service providers, all while minimizing personal data exposure. Importantly, Yivi has developed its own trust scheme (governance framework) which has been operational for years, and they invite other parties to participate as issuers or verifiers in that ecosystem. This makes Yivi a living example of an alternative trust model running in parallel to (and ahead of) the emerging government wallets.

From the outset, Yivi’s philosophy has emphasized openness, privacy, and user control. Yivi implements the Idemix cryptographic scheme to enable features like issuer unlinkability and verifier unlinkability, meaning that no one issuer or verifier can track a user’s activities across different presentations. The entire software stack is open source, and the project is transparent about its architecture. Crucially, Yivi has committed to principles that include never charging end-users for using the app. The idea is that everyone should have free access to secure digital identity tools, regardless of means. This principle aligns well with the EUDI regulation’s stance that wallets should be free for citizens – Yivi was already on that page.

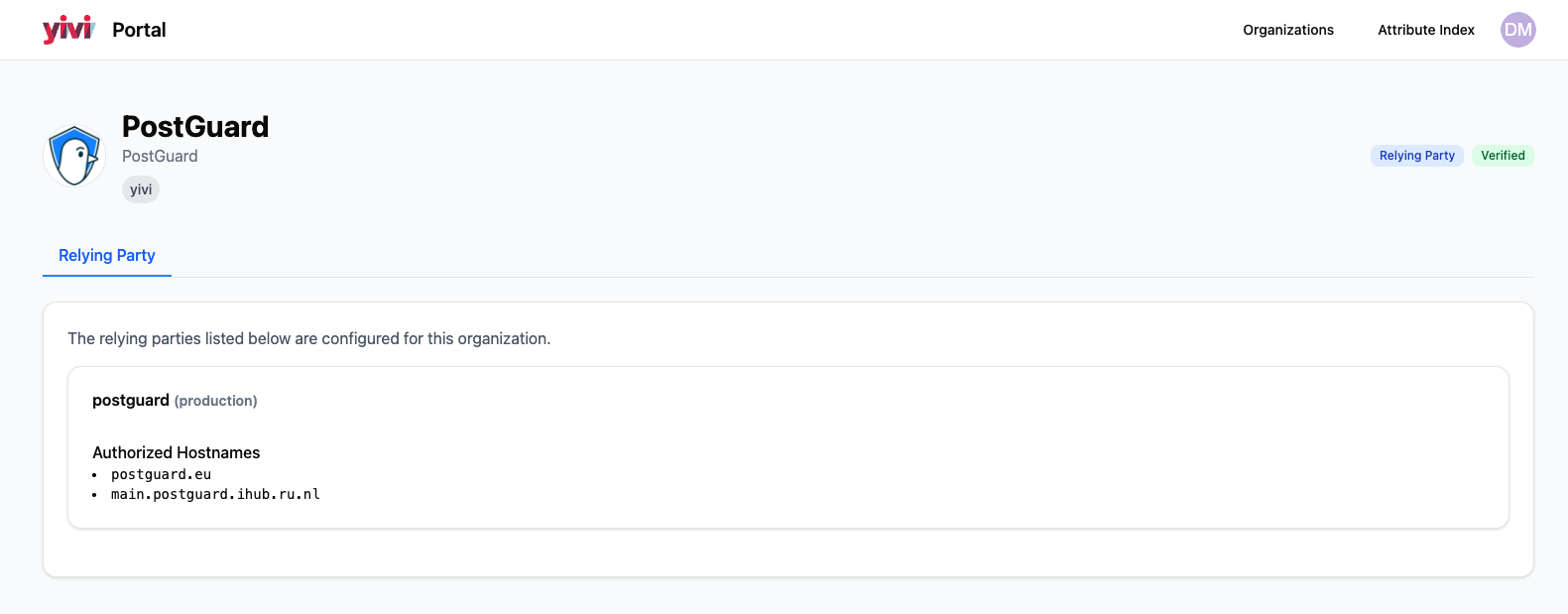

However, Yivi also recognizes that providing these services isn’t free on the backend. Servers cost money, sending out verification codes (like SMS or emails) costs money, and maintaining the system has ongoing expenses. So how to cover those costs without billing users per disclosure? Yivi’s solution is something they introduced recently called the Trusted Verifier program. This essentially is a scheme to vet relying parties (verifiers) and have them share in covering the costs of the ecosystem. Here’s how it works in essence: service providers that want to use Yivi for identity verifications apply to become Trusted Verifiers. Yivi will vet these applicants – checking that they are legitimate, privacy-compliant, and meet whatever criteria to be trustworthy. Once approved, a Trusted Verifier can request and receive credentials from users’ Yivi wallets without triggering warning messages. Users will know these verifiers are “trusted by Yivi,” which improves user confidence.

Now the monetization part: Trusted Verifiers are expected to cover the costs associated with the credentials they request. For example, if a verifier wants to obtain a “verified phone number” attribute about users, Yivi might need to issue that phone number credential to the user. To issue it, an SMS with a verification code must be sent to the user’s phone (to prove the number is under their control). That SMS isn’t free – let’s say it costs €0.08. Yivi’s policy is that the party requesting that credential (the verifier) should pay for it, not Yivi out of pocket and certainly not the user. So in practice, Yivi could charge the verifier a small fee to cover that SMS and a bit towards infrastructure. This way, the more a verifier uses the system (i.e. the more identity confirmations they perform), the more they contribute financially – proportionate to their usage. It’s effectively a transaction-based model, but confined within the Yivi ecosystem and handled via the Trusted Verifier arrangement.

It’s important to highlight that Yivi is not “monetizing the app” in a greedy sense here – it’s about sustainability. They explicitly state that Yivi will remain free and open source, and the Trusted Verifier program is about ensuring the project can sustain itself long-term. By having verifiers bear the cost of issuing and verifying credentials, Yivi creates a virtuous cycle: users stay happy because everything feels free and privacy-preserving; verifiers get high-quality data (with user consent) and a trustworthy reputation by being in the program; Yivi’s maintainers get resources to keep improving the platform (or at least to pay for those SMS messages and servers). They even offer sponsorships or waivers for non-profits or open-source projects that want to use Yivi but struggle with funding, showing an intention to keep the ecosystem inclusive.

Yivi’s model addresses one of the core questions directly: who pays? The answer is clear – the relying parties, called Trusted Verifiers, bear the costs, not the users. In this setup, verifiers pay per disclosure, ensuring that each time user data is shared in a trusted and controlled way, the associated cost is covered by the party requesting it. This approach avoids the need to track every global presentation of a credential. Instead, each verifier accounts for its own usage, paying for the disclosures it initiates. Because only approved verifiers are allowed to request disclosures through authenticated channels, users are protected from misuse: untrusted attempts are flagged in the Yivi app, keeping users informed and discouraging abuse. Importantly, we expect the cost of disclosure to decrease rapidly as the user base grows. At scale, efficiencies in infrastructure, verification processes, and reuse of credentials will drive costs down significantly, making trusted digital identity both sustainable and affordable. The Trusted Verifier scheme thus balances economics, privacy, and trust: technical trust through secure integration, and social trust by keeping users aware of who is accessing their data.

We expect the cost of disclosure to decrease rapidly as the user base grows.

Finally, Yivi is aligning itself with broader standards and the future EUDI framework. The Yivi team plans to support OpenID4VCI and OpenID4VP, the new open standards for credential issuance and presentation. These standards define exactly how wallets, issuers, and verifiers communicate in a secure, interoperable way. By adopting these, Yivi can become compatible with other wallets and systems that also follow the EU’s Architectural Reference Framework. Yivi’s strategy is to remain privacy-first while becoming EUDI-wallet compliant. In practical terms, this means Yivi will be one of potentially several wallet providers that can plug into the Dutch EDI-stelsel and EU trust infrastructure, offering users a choice of wallet apps. Yivi’s trust model (with its open-source scheme) can then “stack” on top of the EUDI model – users could carry government-issued credentials in Yivi alongside Yivi-specific credentials, and verifiers could choose to trust credentials under the Yivi scheme as well as the official scheme. This multi-scheme support is on Yivi’s roadmap, explicitly aiming for multi trust scheme integration so that Yivi can bridge between its original ecosystem and the new EU one.

In summary, Yivi exemplifies how a wallet provider can address monetization in the current climate: keep the wallet free for users, leverage open-source trust frameworks to build confidence, and require the relying parties who benefit from the data to foot the bill in a controlled, privacy-preserving way. It’s a blueprint that others may follow, especially as we transition into the era of European Digital Identity wallets.